Part II introduces the concepts of structure, language, style, and form as they pertain to effective testimony and, together with answering technique, upon which all my recommendations and techniques are built.

Structure – Think Circular, not Linear

Since the structure of the testimony cannot be controlled in cross-examination, this relates to direct examination only. The structure of the direct examination is vital and where you may have a witness that is less than charming, dynamic, or even likable, factors you have less control of, you do have control over the structure of direct examination – so take it.

The overarching concept to impress with an expert is the image of teacher. Teaching is all about retention, which is driven largely by structure (It is also a factor of “form,” which will be given consideration later). The teacher image helps avoid the image of “advocate” and complies with one of the most frequent and positive comments jurors express about their trial experiences – “they learned something.” Not surprisingly, the teacher concept carries with it the obligation to teach. Attention to structure must begin immediately after the witness is sworn.

Following the witness’ background and qualifications, ask a question that prompts a brief discussion of the assignment, such as “What were you asked to do in this case?” This allows the witness to include in the answer words such as “investigate,” “analyze” and “compare” – words that connote a scientific and objective approach to the task – an approach that does not consider a desired end result.

The above answer naturally leads to a question regarding procedures. The answer to that question should be in the form of bullet points. Depending on the length and complexity of those procedures, consider creating an exhibit listing them in the order taken.

Now the witness is ready for the $64,000 question. “Having completed the list of procedures, what did you find?” The witness will now be creating the first headline.

Keeping in mind that jurors will most often forget the details (though they may remember they existed); the goal is to create headlines. During the course of the testimony, the jurors will see the supporting details, but it’s the headlines they will remember and they will remember them in large part through repetition.

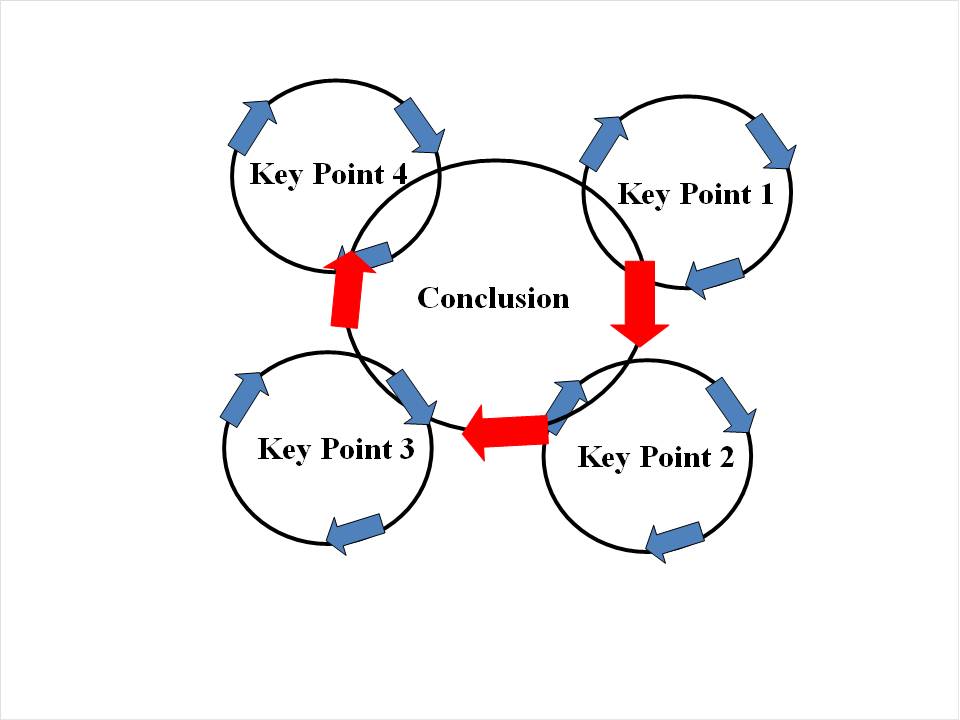

What you will have at this point in the process is the basic skeleton of your direct-examination structure, which consists of a comparison of the procedures with the finding(s). This process will reveal the details of each procedure and its contribution to the ultimate conclusion. The conclusion is the headline, which this structure allows to be repeated many times along the way due to its circular nature.

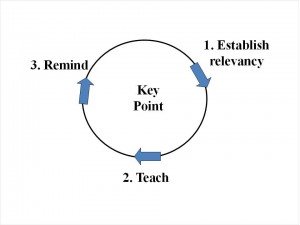

Jurors not only need to understand how a point fits into the big picture, but the importance or relevance of that point to the ultimate conclusion. Establishing the relevance of the point must come first. This will motivate the jury to listen. If the jurors are left with the task of creating their own hierarchy of relevance, your point is at risk. They either won’t do it or they might get it wrong. Do the work for them. A graphic representation of the process reveals the circular structure.

The above represents the teaching of a particular point. It also complies with the principle of primacy and recency. We tend to remember most what we heard first and last, and not so much what comes between them. The process of persuading jurors of the ultimate conclusion is one of continuing the above pattern, taking time to explain how each key point fits together and contributes to the ultimate conclusion.

More “Chunks” of Good Structure

In addition to the primacy/recency effect, attorneys and witnesses should design direct examination around three additional principles;

1. Repetition

2. Chunking

3. Stair stepping

Repetition was mentioned above in connection with the circular nature of good structure. It is also well known, so need to belabor it here. Chunking is a psychological phenomenon that describes the way people learn. Briefly stated, it means we can assimilate a “chunk” more readily than the whole. It is how, for example, we learn phone numbers. We memorize them in groups of three and four; area code, prefix and the four-digit number. Even if phone numbers weren’t written that way, we would still learn them by breaking up the string into chunks.

As described in the discussion of circular structure above, each chunk must start with the establishment of its relevance. It must also be “bite-sized,” particularly when it comes to complex material.

Complexity of the subject matter also drives the need for “stepped learning.” The concept is simple; educate (and elevate) the jurors to the highest necessary level of understanding one step at a time. We all learned math in this fashion. Our progression from simple arithmetic to trigonometry and calculus was by means of small steps that included fractions, decimals and simple algebra. No step can be too high for the jurors to reach or they will be left behind. Keeping in mind a concept from Part I of this series, if the jurors don’t understand the witness, the problem, as they see it, is with the witness and negative perceptions result.

Language

Jurors have told us they don’t appreciate jargon. The obvious solution is to use it as infrequently as possible and to explain it when it must be used. The role of language in expert witness testimony, however, goes well beyond addressing that single issue, and do not assume that avoidance of jargon necessarily means adopting a “folksy” approach. Only a targeted jury research project, in the venue, would determine to what extent that approach is valid.

Consider the issue of relevance. One of the most powerful methods for attributing relevance to a point is through co-orientation. Co-orientation is the process of establishing a common ground with jurors so that they may then be moved to a new position. It is accomplished by means of anecdotal references and analogies. Using those tools, the witness compares the point at issue to something perhaps from everyday life, or at least a reference common to most. This serves several purposes. The witness bonds with the jurors, promotes the image of teacher, raises their comfort level with respect to the issue at hand and ultimately may bring them in tow regarding the conclusion.

Many years ago I was a member of a research team that conducted a weeklong mock trial. Money being no object for this particular piece of research, we incorporated what is known as a real-time response system. You have probably seen them used in focus group studies conducted in connection with the recent general election. Each juror holds a device with a dial that allows them to respond positively or negatively to what is being seen and heard at the moment. A computer compiles the data and creates an average trend line that is displayed on a backstage monitor on a moment-by-moment basis and is recorded on video for later analysis.

One of the most impressive revelations about that system was the showing of jurors’ responses to the use of anecdotal experiences and analogies. In every instance, the trend line would immediately make a positive jump. The only other instance when the trend line would consistently move sharply in the positive direction was when the witnesses offered conclusions and perspectives; words to the effect, “So, what that means is…,” confirming that headlines make the impact.

Style

Think of style (a.k.a. demeanor) as all of the non-verbal elements. It’s not the words; it’s how you say them. It’s your facial expressions and the gestures you use while communicating. It’s your posture and the look in your eye – all those extremely important elements in the arts of teaching and persuading.

We all remember favorite teachers from school. I’m willing to wager none of them were dull, lacking energy, unimaginative or timid. So it is with good expert witnesses.

I was in my hotel room in Minneapolis years ago during a trial and was channel surfing on the TV. The population of the Minneapolis area is known for its relatively high level of education and I happened upon a telecast of the area’s Teacher-of-the-Year Awards. I tuned in just in time to see the Oscar-like announcement of the winner and his acceptance speech. In that speech, he said, “You can entertain without educating, but you cannot educate without entertaining.”

I would add to that observation the concept of engaging. You cannot educate or persuade and audience without engaging them. Non-verbal communication plays a huge role in doing just that. The following is a short list of the most important non-verbal traits of an expert witness:

- Posture – Sitting erect and forward in the witness chair creates a look of confidence. There should be no contact with the back of the chair.

- Eye Contact – Having strong eye contact with each member of the jury contributes to believability. Eye contact is the single-most important non-verbal element of communication with respect to believability and it’s pretty difficult to ignore someone who’s looking you straight in the eye. A client once told me that a post-trial interview with jurors determined the entire case was decided by this one issue. The outcome turned on a lone juror’s decision, who said afterwards, “That one witness looked me in the eye and the other one didn’t and my Daddy told me never to trust anyone who doesn’t look you in the eye.” Enough said, but eye contact with the jury should be reserved for answers to open-ended questions (longer, more narrative responses), to avoid looking as though the witness is watching a ping-pong match. More on this in Part III.

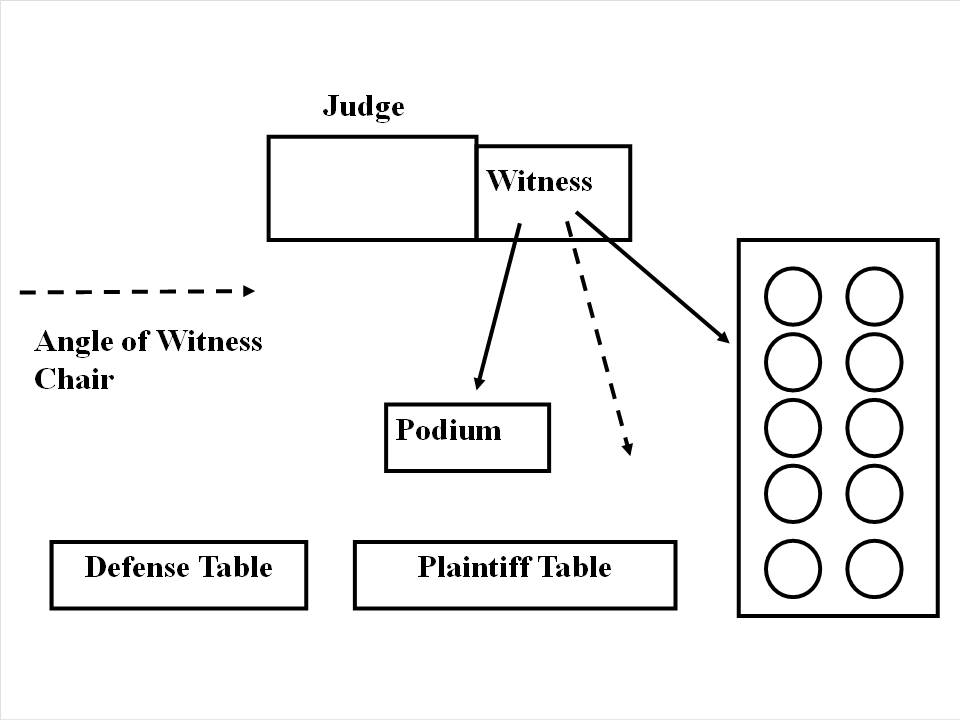

To facilitate eye contact equally with counsel and jury, I advise the witness to turn the chair so as to bisect the angle between counsel and jury. This puts the body in a position where making eye contact is just as easy in either direction.

Many witnesses are reluctant to make eye contact with the jury, preferring the comfort zone of the client attorney. The chair position helps overcome this tendency, but it is often not enough. If you are examining a witness with this trait, pick appropriate moments to prompt the witness, such as with the question, “Would you please explain that point to the jury.” During preparation sessions, the witness should be told when he hears that question it means he’s been ignoring the jury.

- Gestures – Gestures serve two purposes, they help create visual images (the importance of which you will note shortly) and they dissipate nervous energy. In that way, they turn a negative into a positive. (Also on the problem of nervousness, a large gulp of very cold water will tamp down the adrenaline for a brief time, making it a good way to start the examination.)

- Volume – Ideally, the witness should speak with enough volume so as not to need the microphone. Volume from a microphone is just that, volume. Volume created without a microphone takes on a different quality. It is energy.

Energy = Conviction = Credibility.

- Tone – The power of this factor is difficult to explain without demonstrating, but suffice it to say that words often get their meaning from how they are delivered. A witness answering “yes” to a cross-examination question, for instance, can communicate through a matter-of-fact tone that the point of the question was insignificant and, therefore, the admission was meaningless. The same one-word answer, delivered in a tired, muffled tone, particularly if accompanied by downcast eyes and slumped body posture means the cross-examining attorney just scored a major blow.

- Consistency – The witness should appear the same during cross examination as during direct. Same posture, same energy level, same level of confidence, demeanor, attitude, etc. Perceived differences in performance, on these scales, between direct and cross-examination lead to credibility issues with the jury.

Form

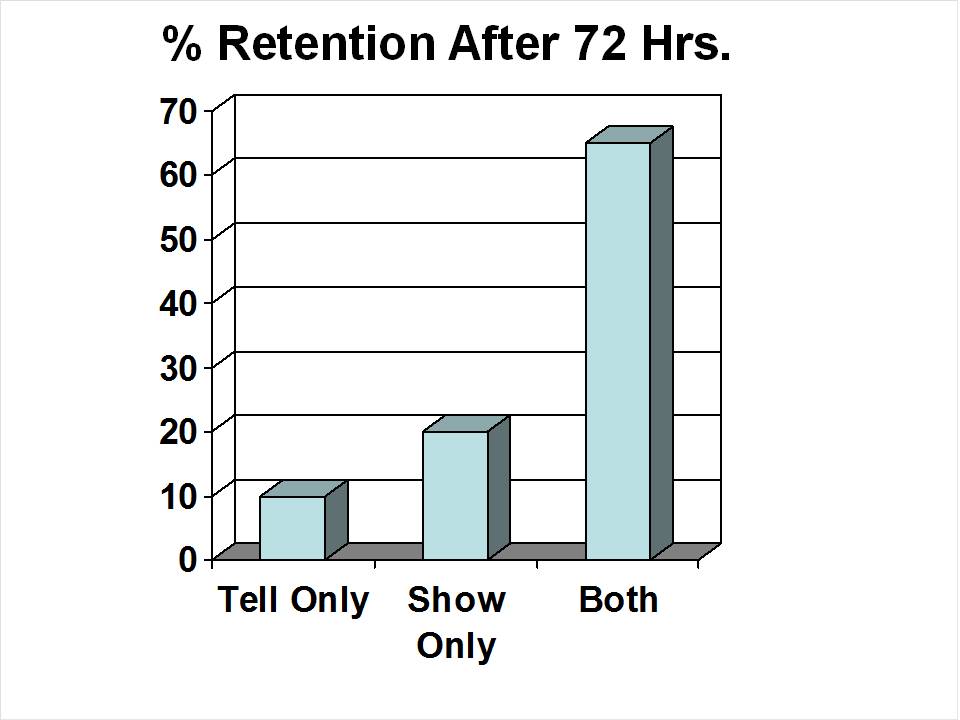

This is where exhibits come into play. Various studies have confirmed that we retain much more from what we see than from what we hear and retention climbs dramatically when the two are combined.

It’s more than a matter of retention; it’s also a matter of motivating the jurors to learn the material. They want to learn, but they want it to be somewhat enjoyable and not too much work.

Trials are becoming increasingly complex, outpacing the ability of the average juror to comprehend the material. The material, therefore, has to be converted to a form suitable to the jury. That means well-designed exhibits, both evidentiary and demonstrative. I caution the reader, however, to rely too heavily on exhibits, especially high-tech exhibits. The most persuasive exhibit in the courtroom should be the witness.

See Part I of this series in “Previous Posts” and look for Part III, dealing with answering technique, in the near future.

For more on Taking the Stand – Tips for the Expert Witness, go to the “publications” tab.

Also, check out my new book, Fixing the Engine of Justice: Diagnosis and Repair of Our Jury System. Select the “Jury Book” tab at the top.